Dialogue Attribution

Dialogue attribution is the fancy name for the words that come at the end (or sometimes the start… or even in the middle) of a line of dialogue. It is the ‘he said’ ‘she asked’ ‘they shouted’ portion of your sentence and there are some general guidelines to abide by when using them. Yes, I don’t like hard and fast rules, but this is one of those areas where playing fast and loose with the guidelines can (and will) see your manuscript thrown across the room by a frustrated editor.

So let’s look at the three rules guidelines …

1

Don’t use them too often

Not every single line of dialogue needs to be attributed thanks to some very handy rules of grammar and social understanding. When two people are having a conversation it is normal to alternate who is speaking. Wendy says something to John and then John says something to Wendy (I’m reading Peter Pan to my daughter at the moment, so complain to JM Barrie about the choice of names). And when John is finished speaking it is either the end of the exchange, or Wendy is going to say something back. Then it’s John’s turn. Then Wendy’s. You get the picture. And since each time a new person is speaking we use a new line, we don’t need anything more than initial attribution as long as the conversation is only this long. Like so:

“I hate Peter, he’s a bit of a jerk,’ Wendy said.

“Come now, he’s not that bad,’ John replied.

“Yes he is,” Wendy said. “He’s a cocky ass.”

John said: “Hmm… yes, I suppose you have a point.”

On those last two lines we don’t need the attribution. It looks crowded and stodgy, even though I stuck the attribution in the middle and at the start. This works better:

“I hate Peter, he’s a bit of a jerk,’ Wendy said.

“Come now, he’s not that bad,’ John replied.

“Yes he is. He’s a cocky ass.”

“Hmm… yes, I suppose you have a point.”

Now of course if Michael were to come along and make it a three way ball game, we would need another bit of attribution, because a reader would naturally assume that the next person to speak would be Wendy again.

“Yes he is. He’s a cocky ass.”

“Hmm… yes, I suppose you have a point.”

“Is not!” Michael said, stomping his foot.

And again we would then have to attribute to show whether it was Wendy or John who replied (Or Peter :O)

“Do you even know what an ass is?” John asked him.

“No.”

“It’s a donkey.”

(Note that neither of those last two needs a direct attribution because using the ‘every new speaker gets a new line’ rule (please oh please never forget that one) we know John has finished speaking, and as there is no attribution the reader naturally assumes it’s Michael as he was the one John was speaking to.)

2

Don’t use too few

The opposite side of the knife-edge from the previous point, but just as important. While using too many makes everything stodgy and slow, using too few is just plain confusing. Even in a two person conversation, after a few lines it can become hard to follow which person is speaking.

“Nice weather we’re having, don’t you think?” Hook said.

“That’s because kids don’t have any imagination these days,” Peter replied.

“Well at least if we have to go out of business we can do it in the warm sunshine.”

“Sure. Hey, did you see what they did to you in that movie, The Pirate Fairy?”

“Don’t even mention that infernal thing. It isn’t so much what they did to me, but that song? It gets stuck in my head for days.”

“Yo-ho imagine the places that we’ll go–”

“Stop it!”

“The finest of tortures.”

“I wouldn’t lord it up, at least I was voiced by the guy who plays Loki. The latest movie about you got only twenty-seven percent on Rotten Tomatoes.”

“I don’t read reviews. People love me.”

Now, I’m not saying that it’s impossible to follow, but it’s certainly not easy. This is where it becomes good to hang a few reminders on there. It doesn’t even have to be direct attribution, just using the character’s name in connection to some action they are performing while speaking can work just as well.

“Nice weather we’re having, don’t you think?” Hook said.

“That’s because kids don’t have any imagination these days,” Peter replied.

“Well at least if we have to go out of business we can do it in the warm sunshine.”

“Sure.” Peter pointed at his old enemy. “Hey, did you see what they did to you in that movie, The Pirate Fairy?”

Hook put his good hand to his brow. “Don’t even mention that infernal thing. It isn’t so much what they did to me, but that song? It gets stuck in my head for days.”

“Yo-ho imagine the places that we’ll go–” Peter sang.

“Stop it!”

“The finest of tortures.”

“I wouldn’t lord it up, at least I was voiced by the guy who plays Loki. The latest movie about you got only twenty-seven percent on Rotten Tomatoes.”

“I don’t read reviews,” Peter said. “People love me.”

Peter pointing in line four and Hook putting a hand to his brow in line six aren’t direct attribution, just gentle reminders using action. These also help to anchor the dialogue to its physical speakers, rather than having the words floating in a void as though the voice has no body. Sometimes it’s more necessary to do this than others. If you have two characters sitting across from one another at a table and the main point of the scene is their conversation, then there is less need to run the action alongside. But if you have two characters creeping through the undergrowth tracking an animal and holding a whispered argument about which one of them should carry the bag of peanuts, then a larger chunk of action will have to run alongside the dialogue or we’ll lose sight of what the characters are physically doing.

3

Almost always use said

Thesauruses (thesauri?) are fantastic things, especially for that word that is on the tip of your tongue and you can’t quite remember what it was, but the one thing you should never use it for – ever – is coming up with interesting dialogue attributions.

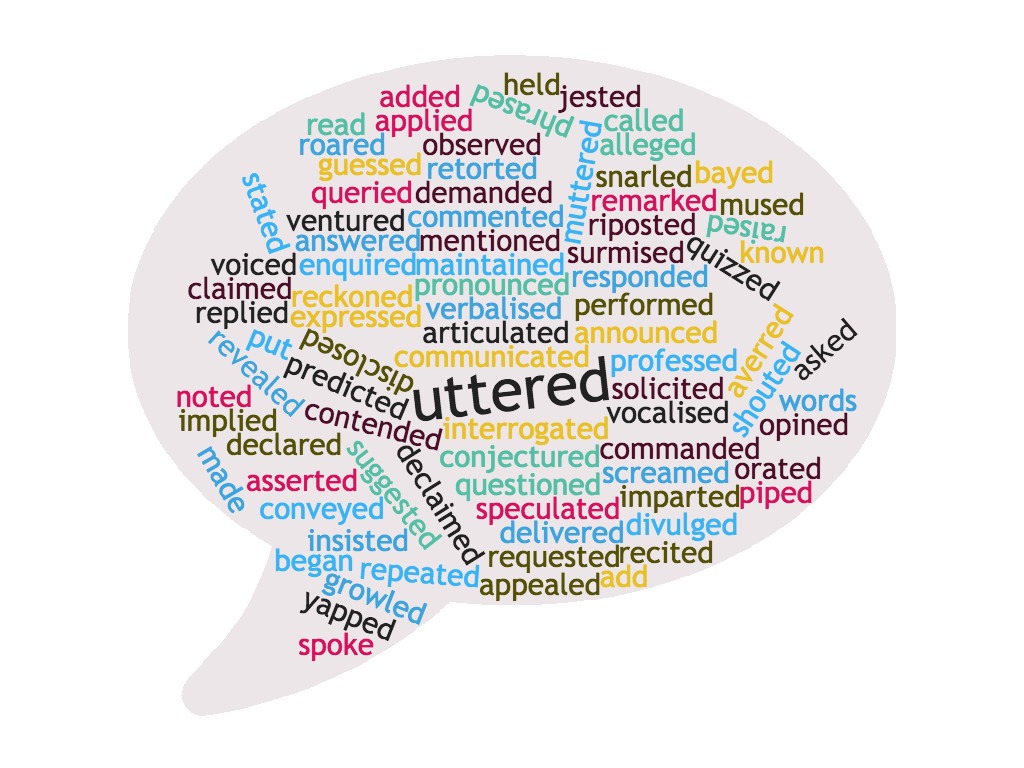

My trusty (and very worn) Oxford Paperback Thesaurus, third edition, published in 2006 (thankfully before words like glamping and budgie smugglers got the green light) informs me that there are numerous replacements for ‘said’ such as:

Urgh ok, I could go on forever, but I don’t think I can handle much more. It is all very colourful and interesting when just considering the great depth of the English language but as soon as you put them into your writing it is distracting. Now, I’m not saying you can never use any of them ever, some of them have a place, but ALMOST ALWAYS USE SAID. Said disappears. It is so mundane and dull a word that readers barely see it. It just vanishes leaving the character’s name or pronoun floating there ready to be connected to their words. Said doesn’t get in the way. It has no agenda. It is only ever trying to be discrete and helpful. Even when your character is asking a question, said is often enough, although asked is pretty invisible too.

So which of the above words are ok on occasion and which should you steer clear of like a plague infested shark pit? Well they fall loosely into three camps.

1

Great used in moderation in appropriate circumstances.

In the first camp we have words like: shouted, screamed, growled, muttered, whispered. Even demanded, ordered and announced could go in there. These are words that convey their own meaning separate to either the golden words said and asked. They are visceral, ‘shouting’ is more than ‘saying with great volume’ as ‘whispering’ is more sibilant than ‘said quietly’. Ordered can give us a sense of authority difficult to attain in certain circumstances, as announced can give flair to the words of a very confident character that ‘said’ could never achieve. These are wonderful words when used sparingly, in appropriate circumstances. The more you use them the weaker they become. So be careful and don’t get too repetitive.

2

Fuck right off and close that thesaurus.

The second camp contains words like: queried, stated, uttered, voiced, remarked and noted, words that are nothing more than direct synonyms of either golden word said or asked, with no other purpose. Use a flamethrower to get rid of these.

3

Stop repeating yourself.

The third camp is the hardest to weed. These are sneaky redundant tags – essentially the attributive equivalent of a tautology. Examples are: guessed, repeated, alleged, divulged and solicited.

“What do you think it is?” Joe asked.

“A washer?” I guessed.

In this situation, the word guessed is totally redundant. The situation and the question mark tell us that I am guessing.

“I think he killed Bob Darling,” Brittany alleged.

No point in telling us it was alleged. Already got that from the words, thanks all the same.

“What does it say?”

“It says: ‘Don’t go anywhere, I’m coming to get you’,” Chad divulged.

Don’t need divulged. It’s trying so hard to be useful and clever, but really it’s just tripping over its own smugness.

You get the idea. These words are sneaky bastards. They will creep into your first drafts here and there and even into your rewrites if you aren’t careful. Prune them. Viciously.

Once you’ve gone through and butchered your mentions and your comments and your queries, there is still one more problem. How do you convey more than just dialogue attribution using just the word ‘said’? Like I said, it’s invisible, it tells us nothing other than who is speaking. How do we know that Johnny is joking if we don’t say “Johnny joked”? And why should I bother piss-farting around with other words when “Johnny joked” gets the point across quickly.

Two reasons

1

One we have already covered – fancy attributions are distracting. But they are also demeaning because of reason two.

2

Show, don’t tell. Don’t tell me he was joking. Let me figure it out myself. Show me his grin. Show me his tongue poking out. Show me the twitch at the corner of his lips as he tries to keep a straight face. Show me anything, just don’t tell me.

“And I thought you were clever,” Johnny joked.

“And I thought you were clever,” Johnny said, his lips split into a grin.

Yes, it’s more words, but there’s a difference between full words and empty words. Don’t take cheap shortcuts.

So what do you need to do? Look at every single dialogue attribution as you go and think to yourself – why haven’t I used said. Or asked. Am I trying to get across something more meaningful as in camp 1? Or am I trying to prove that I’m clever, as in camp 2? It is a natural error. I can remember my early pieces of work being littered with this stuff. I even dog-eared the pages for said and asked in my thesaurus. I spent a long drive bitching to my mum about how JK Rowling couldn’t think of anything more interesting to use in Harry Potter than said. We all make these mistakes. We all have to learn. Do not use a clever or fancy word when a simple one will do. That is you getting in the way of your story.